Hummingbird Migration Takes an Incredible Journey

Updated: Apr. 12, 2023

Learn about the epic hummingbird migration feats of these tiny birds. The diminutive creatures undertake great journeys in spring and fall.

It seems almost impossible that a hummingbird could even exist. A bird no bigger than a large beetle, covered with feathers that glow and sparkle in the sun, it hovers on wings that beat more than 50 times per second, dancing in front of colorful flowers to sip sweet nectar. That would make it remarkable enough. But on top of that, some hummingbirds migrate long distances— hundreds of miles, or even thousands—leaving cold climates for the winter and returning in the spring. Read on for insights into how they accomplish these amazing travels.

Migrating Hummingbirds Travel Alone

Many kinds of birds, from geese to goldfinches, typically migrate in flocks. But hummingbirds travel as loners—each individual navigates on its own. Even young birds making their first southward migration fly solo, without any guidance from their parents. Instead, they rely on instinct.

Hummingbirds have a rapid metabolism, burning energy quickly, so they frequently stop to feed as they travel. Any time they come to a good patch of flowers or feeders, they pause and spend some time tanking up. During peak migration periods, food sources may be swarming with hummers zooming around and sparring in midair as they compete for nectar. At such concentration points, they arrive and leave singly, not in flocks. Each individual’s journey is a series of relatively short flights punctuated by refueling stops.

While most songbirds and some other kinds of birds migrate mainly at night, hummingbirds travel mostly in the daytime, flying fairly low—taking advantage of the warm sunlight and watching carefully for flowers or feeders along the way.

When Do Hummingbirds Migrate?

The timing of a hummingbird’s migration and the route that it takes are dictated mostly by instincts rather than by conscious choices. But those instincts have developed over many years based on what has worked best for the survival of previous generations.

In spring, when hummers are moving north toward their breeding grounds, they have no way of knowing what the weather is like up ahead. Their instincts guide them to arrive at each stop along the way on dates when, in an average year, the coldest weather has passed and some flowers have started blooming. In late summer or fall, when hummers start to move south, they aren’t driven out by bad weather or lack of food. They usually leave while food is still abundant.

In eastern North America, migrating hummingbirds may follow the same general routes in spring and fall, simply reversing directions with the season. In the West, the many mountain ranges—with strikingly different weather at different elevations— make travel more complicated, and many hummers follow very different routes while traveling to and from their breeding grounds. How do hummingbirds find feeders?

Of course, many tropical hummingbirds are nonmigratory, because their habitats provide a good living all year. Even in North America, some are permanent residents. All along the Pacific Coast, some Anna’s hummingbirds stay in the same places year-round, while other species are present only during the warmer half of the year.

Get answers to frequently asked questions about feeding hummingbirds.

Ruby Throated Hummingbird Migration

As the only hummingbirds nesting east of the Great Plains, ruby-throated hummingbirds do a stellar job of representing the family. In summer they are found almost throughout the eastern United States and southeastern Canada. During the coldest months, a few stay in the southeastern states, but the vast majority migrate to a winter range that stretches from southern Mexico to Panama. For many, their summer and winter homes are more than 2,000 miles apart. Learn about the ruby-throated hummingbird range.

When do they leave? Sooner than you may think. Adult male ruby-throats are on the move by late July and early August; most female and young ruby-throats start moving two to four weeks later.

Large numbers move south along the Texas coast in mid-September, and most arrive in Costa Rica in October or early November. In spring, adult males may move north from the tropics by late February. The peak arrival of ruby-throats in the southeastern states is mid-to-late April, and most don’t show up in the Northeast until around the beginning of May.

To accomplish the epic journey, most ruby-throated hummingbirds don’t fly straight north and south. Instead, many move toward the southwest in fall and toward the northeast in spring. Why? Because most are detouring around the Gulf of Mexico. Experts think that some fly straight across the Gulf, a journey of at least 600 miles that could take 18 hours or more, but scientists still don’t know what percentage of the population might do that.

Folks who live along the northern Gulf Coast can help hummingbirds prepare for their arduous journey by providing lots of nectar flowers and sugar-water feeders.

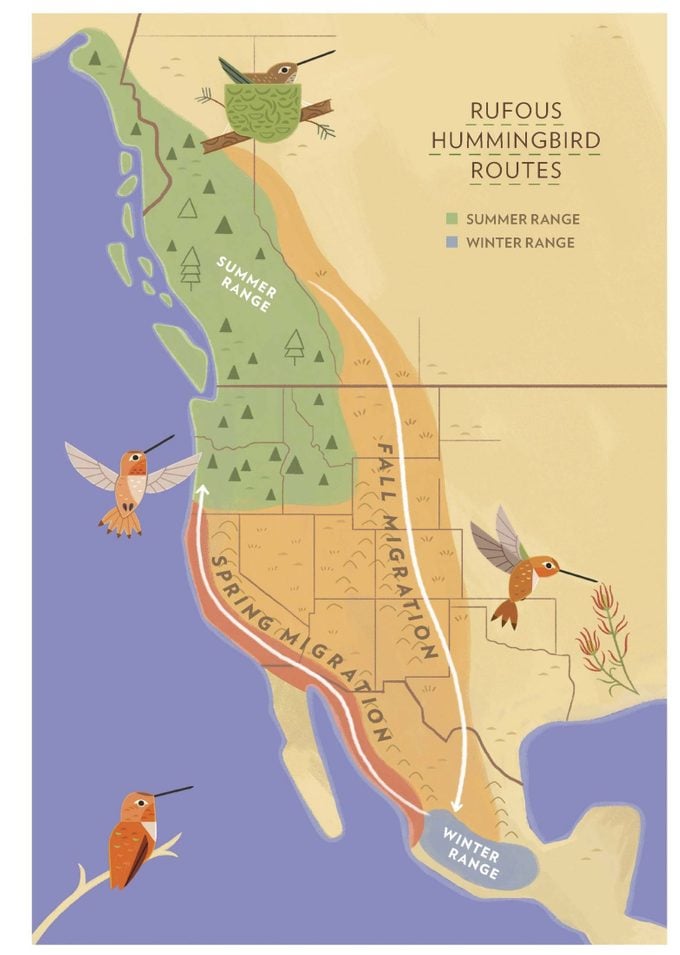

Rufous Hummingbird Migration

A dozen species of western hummingbirds are at least partly migratory, but the rufous is the long-distance champion. Its main winter range is in southwestern Mexico, and in summer some reach southern Alaska—so individuals may travel almost 4,000 miles one way in spring and fall.

Their journey looks unusual on both the calendar and the map. Instead of moving north in spring and south in fall, you could say that they move northwest in late winter and southeast in late summer. Some adult males may leave their wintering grounds in January, since they start to show up in the western United States in February. Rufous hummingbirds travel northwest along the coast and through the lowland deserts, where flowers can be abundant at that season.

By the middle of May they have occupied almost all of their breeding range, which stretches from the northwestern states through western Canada to southern Alaska. Adult males may leave their breeding territories by mid-June, beginning to move east and southeast through mountainous regions. High mountain meadows that had been snow-covered in spring will be filled with flowers by July and August, and rufous hummingbirds swarm there throughout late summer, gradually making their way back toward Mexico.

Perhaps because so many rufous hummingbirds start their southward migration by moving east, they are especially likely to wander to the eastern states in fall. Some have shifted their migratory behavior, and hundreds now spend winters in gardens across the southeastern states, establishing a new migratory route that didn’t exist just a few years ago. The fact that hummingbirds can change to a completely new destination is just one more fascinating fact about these tiny but tremendous travelers.

Why Do Hummingbirds Migrate?

Backyard birders often wonder if keeping a hummingbird feeder up in fall will stop the birds from leaving. The answer is: No. Instincts drive the timing of hummers’ migration, not the availability of food. When it’s time for them to head toward their wintering grounds, they fly away from gardens filled with flowers and feeders. Rarely, a stray hummingbird stays far north in a snowy climate in winter, visiting a heated feeder. But that’s due to faulty instincts—the feeder didn’t keep the bird from going where it should have gone.

Next, learn where hummingbirds sleep at night.